The third part of a triptych on natural pattern formation processes.

In July 1993, John Maddox described in "Nature" under the poetic title "endless ripples on the sands of time" the research work of two Japanese who had succeeded in describing the formation of dunes and sand ripples with the help of non-linear differential equations. Hiraku Nishimori and Noriyuki Ouchi simulated in a mathematical model how the wind in the desert moves grain by grain of sand and arranges them into complex patterns.

At a certain wind strength, spontaneous macroscopic order structures form, caused by collective processes on the microscopic level – that of the sand grain. The simplest physical laws and only the parameters of wind, sand, and gravity are sufficient to generate boundless diversity of forms, which, although imitated by the supercomputers used, could not truly be calculated or predicted. The dune formations and ripple marks on the surface of the dunes are dynamic systems that continually renew themselves through processes of self-organization, leading to recurring similar forms and structures. These pattern formation processes occur quite frequently in nature: the colored patterns on seashells, the markings on the fur of many animal species, electroconvection in liquid crystals, neural activities, and even social processes can be explained by the concepts of nonlinear dynamics. In the preceding sound compositions "sono taxis" and "dripping," similar phenomena were discovered in the interaction patterns of frogs and grasshoppers, as well as in the drip patterns of coupled water taps. The piece "windscapes" completes a triptych of three sound images on the theme of nonlinear dynamics.

First, a quiet, delicate rustling is heard – sand trickles through an hourglass, focusing the listener's attention, images emerge in the mind's eye: wind picks up, rattling wind noises escalate, and gradually the entire spectrum of imaginable wind sounds rushes through the hourglass, before the storm abruptly ceases and the listener finds themselves in a dried-up salt pan amidst a sand desert, where gusts of wind drive scattered sand grains.

The desert, as a landscape reduced to its most essential and primal elements, as a place of introspection, of listening within oneself, is the starting point of "windscapes." The sand desert, with its breathtaking beauty and simplicity, embodies the ideal of a landscape shaped by the wind. The sea of dunes and the aeolian modulations of the sand evoke the vast emptiness of an ocean, whose silent sand waves are endlessly modulated by the wind in boundless diversity. The flowing forms and patterns of the sand seem to continue endlessly – like time, for which sand has served as a measure since ancient times.

The wind varies in its original direction, temperature, dryness, duration, and seasonal occurrence – even in antiquity, the winds that arise over the Sahara were given different names: Buran, Harmattan, Sirocco, Samum, etc. The different qualities of the wind correspond in "windscapes" with soundscapes of the desert, which become acoustically perceptible only through the wind. Sand deserts, rocky deserts, and mountainous deserts, which make up the majority of all dry areas on Earth, as well as ghost towns buried by dunes, provide the backdrop for the six stations traversed in "windscapes": The Vlei, a dried-up salt pan with cracked clay shards and hollowed-out clay soil; Knotty desert flora, whose dry branches rattle in the wind; An abandoned house where glass shards clatter in the window frames and loose hinges flap in the wind; A mountain cave and tube-like hollow spaces that sing in the wind; A diamond city buried by sand dunes, where loose metal fittings and wires clang and the sounds of flowing sand escalate into the phenomenon of the booming dune; Finally, the rocky desert, where rock formations crack open due to intense sunlight and the wind blows small stones over the hollow rock. In all soundscapes, the wind plays with objects, sweeps over the ground, carries sand, makes various sound bodies sing in the air current, and allows us to sense the forms of an archaic landscape and its physical structures. The typical howling and whistling of the wind suggests that the different sound spaces resonate with their own moods and tones, and that the spatial distribution of self-sounding objects reveals the path of the wind.

In addition to the real soundscapes, two types of sound installations provide the essential compositional material for "windscapes": a 20 to 30-meter-long wire stretched by the wind and translated sand ripple photographs into rhythmic sand noises using tactile transducers. The wire forms a closed system that, solely through interaction with the wind, generates tonal and rhythmic effects and is associated with the macroscopic structures of the dunes. The sand noises represent the acoustic translation of microscopic sand ripple structures, whose rhythmic behavior has been synchronized with that of the wire.

The discovery of the rhythmic sound properties of various wires is credited to Uli Wahl from Weinheim and is presented here to a broader audience for the first time. A 20 to 30-meter-long metal wire or a twisted flat wire is stretched perpendicular to the wind, causing the wind to resonate the wire in the natural harmonic series depending on its strength. The particularity lies in coupling the tone modulated by the wind of the wire with a second thin wire, which is knotted into the wire near the suspension point and connected to a resonator with a soundboard. This second wire resonates in its own pitch and harmonic spectrum. Through the interaction of the two strings, the tones escalate into polyphonic sound structures with increasing wind, moving back and forth echo-like on the wire and leading to a pulsating behavior. The pulse speed depends on the length of the wire: the longer it is, the slower the echo. The sounds are picked up with a piezo microphone directly in the resonator, which acts as an amplifier and also protects against stray wind. All wire sounds used in "windscapes" are original recordings by Uli Wahl, with no alterations or technical tricks applied. The clear, penetrating tones of the wires can be envisioned as a representation of the glaring light of the desert sun, and the slow swells and fades of the harmonies sound as if the interwoven lines of the dune crests are being traced.

Analogous to the flowing contours of the dunes, the sand ripples on the surface represent their embryonic primal state, in which the macroscopic structure and layout of the dune formations are already determined. The aeolian modulations of the sand trace the paths of the wind perpendicular to the dominant wind direction, which, depending on the shape of the dunes and the changing wind directions, constantly redistribute, merge into each other, or are overlaid by patterns of different frequency and amplitude. The ripple marks move in wave motions, centimeter by centimeter, across the dune ridges on a daily basis. The challenge was to make this slow-motion movement of the sand ripples acoustically perceptible. The idea was that the sand waves crash against spatially distributed sound bodies, which act as acoustic detectors to capture the temporally staggered impact of the ripple marks. Various sand ripple photographs were selected, focusing mainly on transitions with period splitting and many ramifications. These photographs were transferred to the computer, allowing individual sand ripple lines to be assigned to specific sounds. The time window of a music program repeatedly scanned across the images, advancing along the main direction of the ripple lines with each iteration. This process extracted control information for each individual sand ripple from the photographs, making the temporal changes – the divergence and convergence of the ripple marks – audible and casting them into a rhythmic progression.

Since sand in the desert is transported by the wind either through creeping ("creep") or by short airborne movements ("saltation"), sonic equivalents were sought for both modes of transportation. For the creeping movement of the sand, paper sheets, metal plates, and glass panes were placed horizontally in elastic suspensions, onto which the control information of the sand ripple patterns was transmitted via so-called "body shakers" (vibrating speakers). Low-frequency pulses caused the sand applied to the resonant surfaces to trickle in rhythm with the ripple lines, and by using different grain sizes of sand, a different timbre could be assigned to each sand ripple. The low-pitched control pulses were later filtered out of the signal since the frequency range was not relevant for the sound of the creeping sand. Interestingly, the sand often spontaneously accumulated into dune-like formations on the vibrating resonant surfaces, which moved like accelerated shifting dunes when slightly tilted. This phenomenon is reminiscent of the research conducted by Ernst Chladni around 1780, who generated geometric figures by scattering sand on glass and metal plates and then stroking the edges of the plates with a violin bow. However, Chladni's acoustic figures only occur with square and circular plates. In the case of differently shaped plates or the use of rhythmic information instead of a constant tone, the behavior of the sand appears to be mysteriously related to the pattern formation processes responsible for the formation of dunes and sand ripples.

For the movement of sand through the air, countless individual recordings of blown sand grains colliding with different sound bodies were made, and they were temporally associated with the corresponding control information. For an organic, natural sound progression, it was important to record various variations of sand grains and gusts of wind and to strike the used sound bodies with the sand at different positions. Objects made of wood, stone, glass, and metal were used, and their sounds were then combined with the noises of the creeping sand. Additionally, wind noises from whirlies - plastic tubes swirled through the air - and short blowing sounds from bamboo flutes and bottle necks were used.

As in the previous sound compositions "sono taxis" and "dripping," the "drifting pattern" montage technique was used in parts of "windscapes" in the rhythmic passages. This looping technique follows the self-dynamics of nonlinear processes, whose developmental laws are repeated with a certain fuzziness. Along the rhythmic pulse of the sand ripple patterns, the acoustic loop continually moves with a slight offset along the time axis, thereby reinterpreting the material rhythmically anew. One could imagine this montage technique as akin to the silhouette technique, where a specific vertical area is cut out from multiple copies of an image, and each area moves a certain distance to the right. When these individual cutouts are lined up, a horizontally stretched image is created. The result is rhythmic progressions, whose pulses move kaleidoscopically to each other through constant shifts, rhythmic accents or counts blur, and a hypnotic tension field of repetitive patterns emerges.

The nuanced changes and imperfections in the "blurred" rhythms symbolize the concept of nature as a network of intertwined rhythms and time scales, where only similar but not exactly identical processes can be observed ("The beat repeats; the rhythm renews." – L. Klages). The interaction of repetition and subtle changes in the sand ripple patterns points to a cyclical perception of time: stepping out of the linear flow of time by freezing the moment in continuous, self-renewing repetitions, which, like the endless ripples on the sand of time, move grain by grain against the horizon.

Production: Deutschlandradio Berlin, Hörspiel Werkstatt

Editor: Götz Naleppa

Premiere: December 7, 2001

Duration: 33 min.

The author

Andreas Bick, born in 1964 in Marl, began learning guitar through self-study at the age of 14. Since 1983, he has been residing in Berlin. He studied sociology for a year and concurrently had numerous performances as a musician in a rock band, receiving instruction in harmony and music theory.

In 1986, he produced his first sound compositions in an experimental studio funded by the Berlin Senate. In 1988, he participated in rehearsals and concerts on a reconstruction of Oskar Sala's Trautonium. Since 1988, he has worked as a sound engineer and music producer in various studios, contributing to the design and equipping of recording studios. Between 1992 and 1996, he worked as a music educator, establishing the model project "Hip Hop Mobil."

Bick has published works on alternative music education concepts within the hip-hop culture realm, taught in vocational training programs, and organized music exchange projects with the Goethe-Institut in Cameroon and Los Angeles. Since 1996, he has worked as a freelance film music composer for cinema and television productions. Notably, he composed orchestral scores for the films Pinky and Playboys, the theme music for the award-winning television series Sperling, as well as music for several episodes of Tatort and the series Berlin, Berlin, Klinikum Berlin Mitte, and Kids von Berlin. Since 1999, he has been creating audio pieces for various radio stations (WDR3, Deutschlandradio Berlin, Radio Kultur, Ö1, etc.).

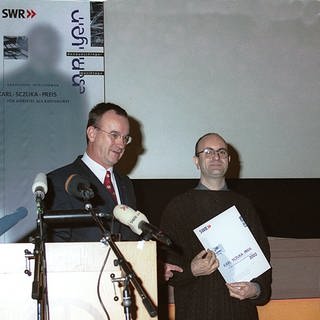

In 2000, Bick was awarded the Prix Ars Acustica from WDR for his sound composition "Dripping." In 2002, he completed the triptych on natural pattern-forming processes, consisting of the works "Sono Taxis," "Dripping," and "Windscapes," with the premiere of his latest audio piece "Der Klang der Haut" on WDR3 in November 2002.