a radiophonic speaking oratorio for speaker, noises and piano

Yes, if I were Hugo Wolf, that would be good.

introduction (by Gerhard Rühm)

the text hugo wolf und drei grazien, letzter akt (hugo wolf and three graces, final act) can be traced back to my long-standing intention to write a speaking peace for five people, each speaking words based on one of the vowels U, O, A, E, I, which gradually accumulate to form five-part vocal sounds.

after making extensive lists of single-vowel words, i naturally had to find a thematic focus for this basic formal concept in order to give the whole an inner frame. i finally decided to refer to a well-known historical personality whose name already contained the starting vowels U and 0. after some time, i ended up with hugo wolf, who also proved a lucky hit from a biographical perspective, in the course of his embittered life - embittered because of an early syphilis infection that led to insanity - hugo wolf had three intense romantic relationships: with valentine (vally) franck, melanie köchert-lang and - as a turbulent intermezzo - the singer frieda zerny. It is a peculiar coincidence that the first syllables of the three women's first names all contain the vowels A, E and I. if one gives hugo wolf a dual role, which seems quite logical considering his consciousness-splitting illness, the three 'graces' (a, i, e!) supply the rest of the required five vowels in an comprehensible manner.

there are very few one-vowel words with U or O; most have an E. to create a quantitatively balanced relationship between the five groups of words, i assigned fifty different words to each voice - U and 0, with twenty-five words each, are reserved for hugo wolf and his alter ego as a dual role, naturally such a reduced selection of words cannot be used to produce an extended descriptive text, let alone a continuous dialogue, but that was by no means my aim. so, although this is a more or less free portrait of wolf, it does contain - both in the text and the noises used - isolated anecdotal allusions to biographically documented events and certain characteristics of hugo wolf.

the supplement 'last act' to the title of my 'speaking oratorio' - this term comes from the baroque poet johann klaj, co-founder of the linguistically creative nuremberg pegnitz flower society in nuremberg - refers to the fact that the last phase of wolf's life is the focus here, defined by hallucinations on the one hand and an increasing physical and mental torpor on the other. the appearance of vally, melanie and frieda should therefore be viewed as a hallucinatory projection, while the reduction and semantic blurring of the word selection, in its increasing superimposition, can be interpreted as a model process of mental drying-up: at the end, spoken words are lost in pure sound.

initially, the decision to subsume the three female figures in the piece under the collective term 'the three graces' was merely a result of playing with language, later on, however, i found it appealing at least to hint at the mythological background to this word, which is meant slightly ironically in colloquial language, as an erotically connecting element. [...1 in the present radio piece, the language of the three graces already has little in common with real people, in this context they should be understood as retrospective projections, wishful thoughts in wolfs mind. like his alter ego, their merely remembered presence forms a part of himself. [...]

even if the radio play, which also exists in a theatre version (published by ritter verlag, klagenfurt-graz, 2014), is not conceived as a literary portrait of hugo wolf, one occasionally finds parallels with biographical facts - some of them were deliberate, while others seemed to grow of their own accord from the language material that had been put together. although the focus is on the last part of hugo wolf's life, past and present events overlap as current experience in a hallucinatory perception.

in the following, i will elucidate a few of the biographical references.

the pendulum clock, there are numerous accounts of wolf's hysterical sensitivity to sounds and noises. for example, a landlady supposedly once threw him out of his flat when she caught him trying to detach the pendulum because his nerves were frayed from the clock's incessant ticking.

we also know about his overwrought reactions to animal sounds. from may 1895 onwards, he had a hunting rifle leaning against his desk; he used it to silence birds whose singing disturbed him while he composed, he wrote the following about this to melanie köchert: 'Today I killed a finch that was mistreating me horribly. But when I saw the poor fellow lying there dead. I was overcome with great anxiety and wished most vigorously that he were still alive.' and later on: 'Meanwhile I have been regrettably forced to do away with another few feathered pests. Oh, one grows accustomed to everything.'

he was no less indignant in his reaction to applause at public performances, in her Memories of Hugo Wolf, rosa mayreder writes: 'The usual form in which appreciation is expressed, namely applause, hurt him; before every concert at which he had to accompany his own songs, he cursed the ghastly noise that tears one's ears apart after every piece, and it was not his custom to bow. At the last concert he gave - on 22 February 1897- he seriously wanted to print the warning "No applause allowed" in the programme, and only the most urgent appeals of his friends could dissuade him from doing so.' the children's piano symbolizes the pathological regression to an infantile stage. when hugo wolf wanted to share his piano arrangement of the meistersinger prelude by his idol richard wagner, which he had once been able to play perfectly, with a group of friends, his memory already failed him after the first few bars; after futile attempts to pick up the lost thread, he broke off the performance in distress. modifying this incident, i replaced the meistersinger with his own opera the Corregidor, whose opening augmented triads are relative chords of the diminished seventh theme from the rejcha fugue that appears later: neither of the intervallic steps go beyond repetition, they remain trapped within themselves, which - in a metaphorical sense - corresponds to hugo wolf's obsessive psychopathological state.

the four-part fugue by the czech composer antonin rejcha (1770-1836) comes from his amazingly 'experimental' 36 fugues op. 36, which were written during his stay in vienna from 1802-1808.

the sheet of paper 'dancing' (flapping to the ground). in wolfs life, periods of frenzied inspiration alternated with a paralyzing lack of ideas. he could brood over a piece of manuscript paper for hours without writing down a thing. the trigger words 'dance' and 'naked' in vally's text can also be biographically placed: in 1899, in the sanatorium, wolf was transferred to a latticed bed from which he often jumped out, impossible to restrain, before dancing about the room naked.

the thundershower and valty's silencing 'stop!' [halt] refer to wolf's megalomaniacal fantasy in which he was jupiter and had power over rain and sunshine; following the principle of single-vowel allocation, the preceding imperative 'let it rain!' [es regne] is assigned to melanie. her verb 'appoints' [ernennt], on the other hand, refers to wolf's delusion that he had been appointed director at the vienna court opera instead of gustav mahler.

one can see the repeated appearance of the verb 'window' [Fenster], as well as the sound of the smashing pane of glass, as a chronological anticipation of melanie's fatal jump — she could not come to terms with wolf's death (1903), and jumped out of the fourth-floor window of her house in vienna a few years later. [...]

for hugo wolf, train journeys sometimes seem to have been associated with unpleasant experiences and melancholy feelings, in august 1896, for example, when a speck of soot that had got in his eye on a journey to graz was removed, a reflective pupillary rigidity was diagnosed in both eyes — an unmistakable symptom of progressive cerebral paralysis. [...] the fact that the title figure has a dual role already makes it clear that this piece, whose text reprises and ensembles lend it the character of a libretto, but which is simultaneously— in its rhythmically fixed form — the 'oratorio' itself', is not a realistic psychological radio play. words like 'tears' or 'anger' are not illustrated here through expressive speech, but delivered in an emotionally neutral fashion, though neither drily nor mechanically — that is to say, there is recitation rather than declamation.

certain hallmarks of 'concrete poetry' such as radical reduction of the language material and a dissolution of the hierarchy of the syntactic system of rules for the sake of the free availability of the individual word (or phoneme) perhaps recall, at a fleeting glance, the linguistic peculiarities of schizophrenics. an extended text like the present one, in which the restriction of the word selection was methodologically intensified through the singlevowel selection principle, can reinforce this impression still further, with reference to biographical facts from the title figure's life, such a treatment of language transpires not as a mistake, but rather as thematically-motivated and entirely justified, in the 'final act', wolf's thoughts revolve obsessively around the same words, around three emotionally central figures in his life (the three 'graces') — a psychopathological behaviour that falls into the category of speech phenomena known from schizophrenics: verbigeration, the stereotypical repetition of words and fragmentary phrases taken out of their respective contexts and the blurring of their meanings, as well as agglutination, the temporal isolation of individual words, the disintegration of the speech flow extending even to a total loss of language. [...]

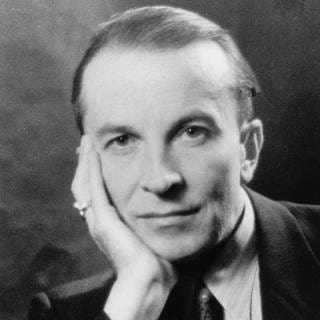

About the author

Gerhard Rühm, born in Vienna in 1930, exponent of international concrete poetry, sound poetry and one of the most productive realizers of the New Radio Play. Composer and visual artist. Co-founder of the legendary avant-gardist Vienna Group. In the 1950s and 60s his activities were initially mostly literary, and he developed poetry further especially in threshold areas: into visual art (visual poetry, gestural drawings, visual music, photo montage, book objects), into music and acoustic art (lecture and tape texts, chansons, documentary melodramas, tone poems and radio pieces). From 1972-1996 he was a professor at the Hamburg Academy of Visual Arts. Fundamental theoretical contributions to the New Radio Play and Acoustic Art. He has been awarded numerous international prizes for his works.